The term (offshore company) or (offshore corporation)

is used in at least two different ways. First, an offshore company can be a reference:

A company, group, or sometimes a division engaged in relocating business processes abroad.

International Business Enterprises (IBCs) or other legal entities are covered by a law prohibiting the local economic activity.

Previous use (companies established in an offshore jurisdiction) is probably the most commonly used term. In individual cases, it may also use this term for companies operating offshore oil and gas operations.

The use of the words “offshore” and “enterprise” may differ for companies and similar entities included in an offshore jurisdiction.

Which jurisdiction is considered offshore often depends on perception and degree. For example, classical tax haven countries such as Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, and the Cayman Islands are primarily offshore jurisdictions. Companies included in those jurisdictions are regularly labeled as offshore companies. Then there are small, medium-sized countries or territories, such as Hong Kong and Singapore (sometimes referred to as “middle-coast” jurisdictions), which, although large financial centers are not a zero-tax system. Finally, classes of industrial economies can be used as part of a system of tax incentives, including countries such as Ireland, the Netherlands, and especially the United Kingdom, which comment on corporate investment and the use of the British overseas territory. In addition, in the federal system, states that act as a classic offshore center may cause corporations formed in them to be marked offshore, even if they are part of the world’s largest economy (e.g., Delaware in the United States).

In addition, the term “company” is used freely, and its scope can be seen as any kind of artificial entity, including not only corporations and companies, but also potential LLCs, LPs, LLPs and sometimes even partnerships or even trusts.

Classification of offshore companies

The history of offshore was broadly divided into two categories. Some companies were legally exempt from tax in their jurisdiction at the time of registration if they did not do business with the residents of that area. Such companies were commonly referred to as international business organizations or IBCs. The British Virgin Islands initially popularized such ones, but the model was widely copied. 2000 The OECD was initially a pro-government initiative, endorsed by the Court of Appeal, the United Kingdom (United Kingdom Virgin Islands and Gibraltar) court in the United States. On the other hand, the IBC is also subject to the courts of Belize, Seychelles, BVI Anguilla, and Panama.

The history of offshore was broadly divided into two categories. Some companies were legally exempt from tax in their jurisdiction at the time of registration if they did not do business with the residents of that area. Such companies were commonly referred to as international business organizations or IBCs. The British Virgin Islands initially popularized such ones, but the model was widely copied. 2000 The OECD was initially a pro-government initiative, endorsed by the Court of Appeal, the United Kingdom (United Kingdom Virgin Islands and Gibraltar) court in the United States. On the other hand, the IBC is also subject to the courts of Belize, Seychelles, BVI Anguilla, and Panama.

Alternative to IBCs, countries with tax systems have broadly similar effects: as long as the company is operating and the profits are not returned, the company is not taxed in the one and same country. When the home jurisdiction is considered an offshore jurisdiction, such companies are generally considered offshore companies—for example, Hong Kong and Uruguay. However, in the case of non-national systems, this is not a matter of law and order: the United Kingdom has a policy similar to that of a company tax.

Separately, an offshore jurisdiction does not tax any tax on companies, so their businesses are exempt from fattening tax. Historically, the best examples of these countries have been the Cayman Islands and Bermuda, although other countries such as the British Virgin Islands have now switched to this model. Depending on the relevant financial perspective, they may fall into one of the two previous categories.

There are five (non-consecutive) restrictive conditions in the definition of an offshore company:

(1) The government of the company’s country does not charge an indirect tax to the OAC (but the OSC government pays an annual fee).

(2) The OSC does not have its own office (address), staff, means of communication, etc.

(3) There are examples of useful elements for anonymity, such as the acquisition of shares and the absence or limited disclosure of liabilities.

(4) This means that the OAC must have a representative (registered representative) and an office address (registered office) in the inclusion district.

(5) Separate laws and regulations apply.

Full List Of Countries

Covered By Our Service

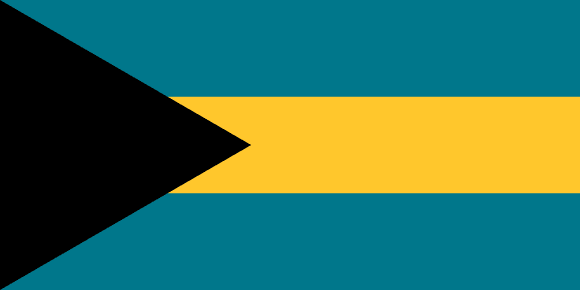

Bahamas

From 1380€

Belize

From 580€

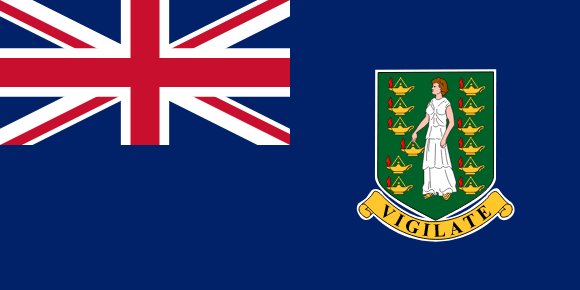

British Virgin Islands

From 800€

Canada

From 1300€

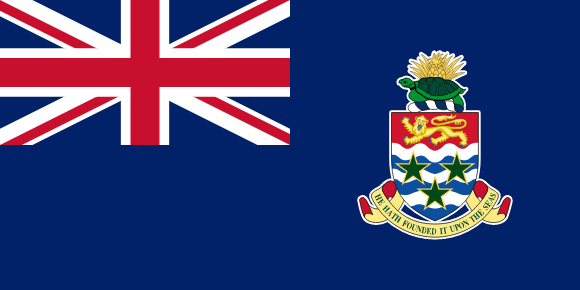

Cayman Islands

From 2840€

Costa Rica

From 2100€

Cyprus

From 1430€

England

From 390€

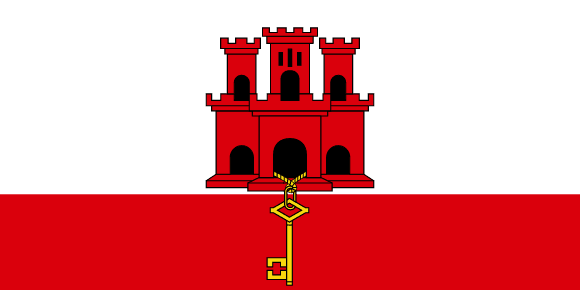

Gibraltar

From 2450€

Ireland

From 1100€

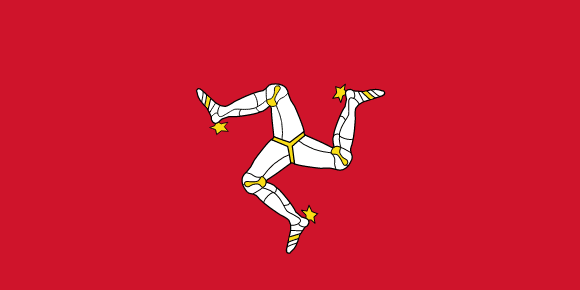

Isle of Man

From 2500€

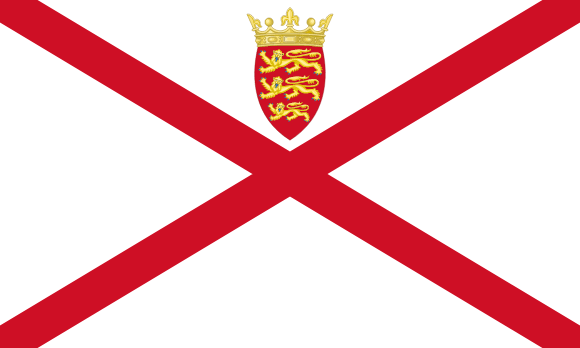

Jersey

From 2430€

Labuan

From 2250€

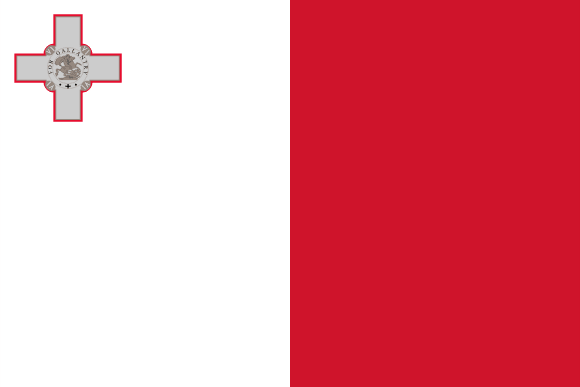

Malta

From 2800€

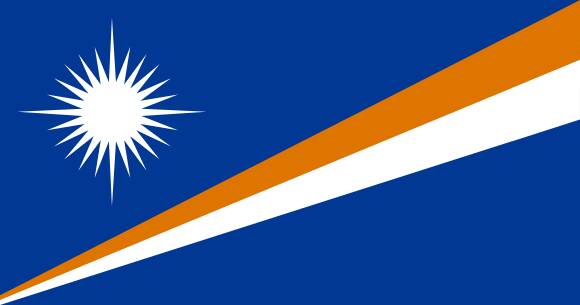

Marshall Islands

From 800€

Mauritius

From 2400€

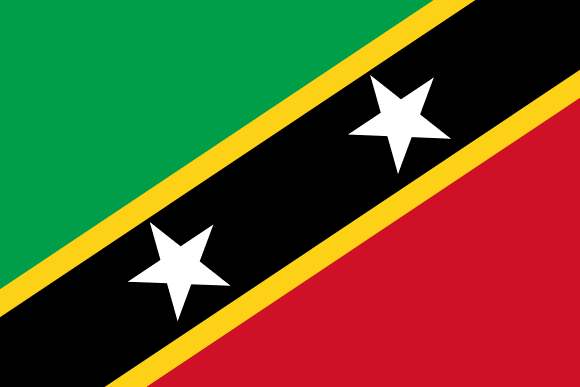

Nevis

From 900€

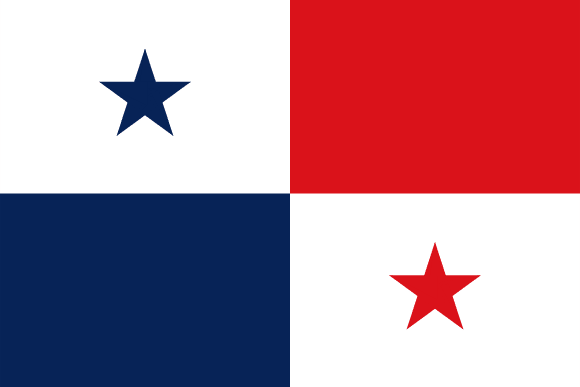

Panama

From 1200€

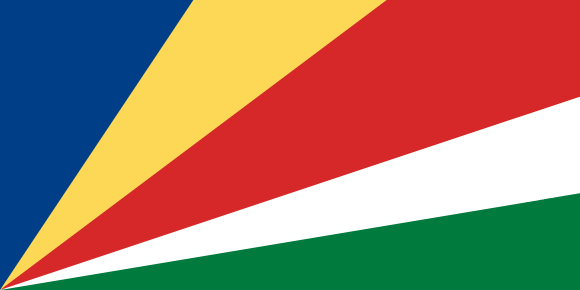

Seychelles

From 349€

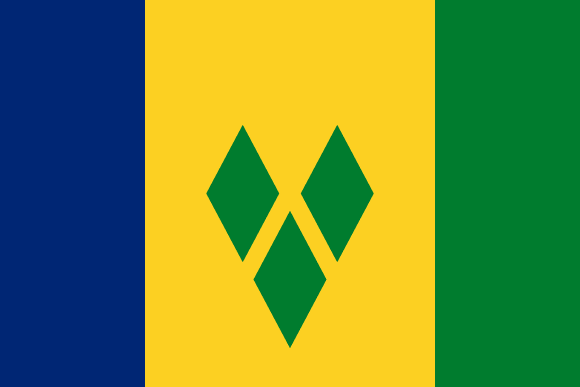

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

From 1090€

Offshore company features

Although all offshore companies differ slightly depending on the corporate law of the relevant jurisdiction, all offshore companies have some key features:

They do not pay heavy taxes on the jurisdiction of their home. (UAE)

Corporate governance will be designed to promote business flexibility.

Controlling a company’s operations will generally be easier than in a developed country.

The absence of taxes or regulations in the original jurisdiction does not exempt the company in question from taxes or regulations abroad.

We use offshore companies for a variety of commercial and personal purposes. Some are legal and cost-effective; others are harmful or even criminal. There are frequent allegations in the media about the use of offshore companies for money laundering, tax evasion, fraud, and other types of white crime.

We have also used offshore companies for a variety of commercial transactions, from generic holding companies to joint ventures and listed vehicles. In addition, offshore businesses are widely used with personal assets to reduce taxes and privacy. Using foreign companies, especially tax schemes, has been controversial in recent years. Many high-end companies have stopped using offshore entities in their group structures due to public campaigns to give such companies “fair shares.

We know details of the use of offshore companies to be difficult to find because most companies are opaque (and because, in many cases, companies are specifically used to maintain the confidentiality of a transaction or individual). However, it is widely believed that offshore companies are mostly used for tax mitigation and/or regulatory arbitrage, although there are some suggestions that the value of the tax structure may be lower than previously thought. Other legitimate uses of offshore companies include joint ventures, SPV financing, exchange instruments, controlling companies, and uses as assets management structures and trading instruments.

Cross-border use between offshore companies (i.e., depending on a person’s approach to globalization and the soundness of tax planning that may be considered legal or illegal) includes investment funds and personal assets as instruments.

Register a company

1. Choose a suitable for your objectives and goals jurisdiction;

2. Choose a suitable for you organizational-legal form;

3. Choose a unique name;

4. Decide on the composition of the founders, shareholders, directors;

5. Decide on the legal address for your company; In some of the jurisdictions a local representative is also needed;

6. Prepare all required documents, forms, decisions and applications;

7. Submit the documents to the registering authority, tax and other required authorities;

8. Pay the government, notary, stamp duties;

9. Receive a package of documents for registration. If the documents are not in English language and you also planning on operating outside of the jurisdiction of registration, then also translate and legalize the documents;

10. Appoint an accountant;

11. If you are planning on doing a kind of business which requires an allowance/license, then obtain one.